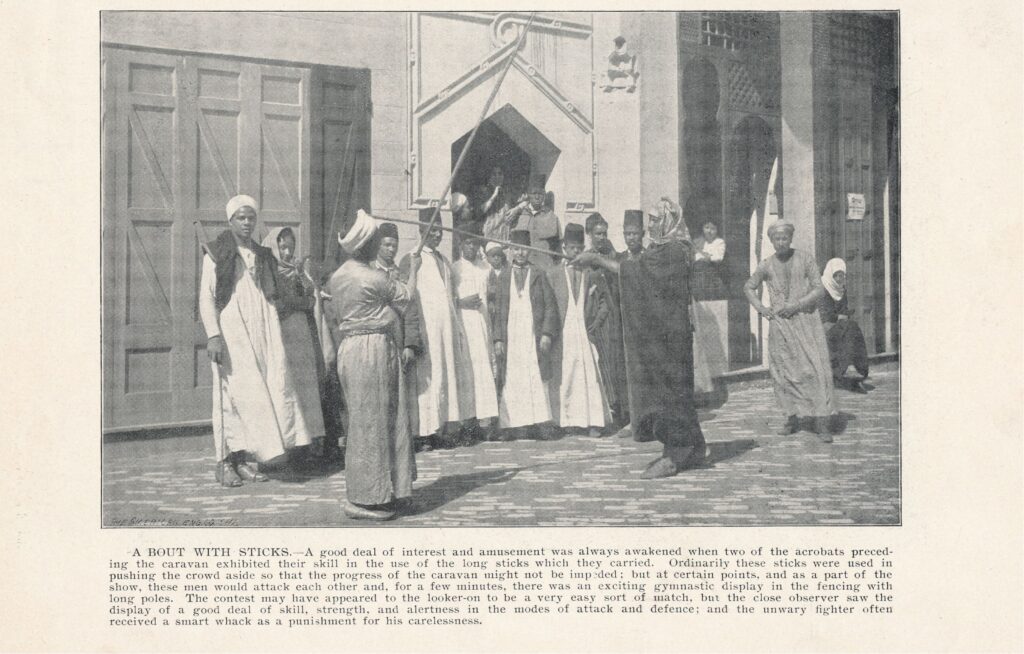

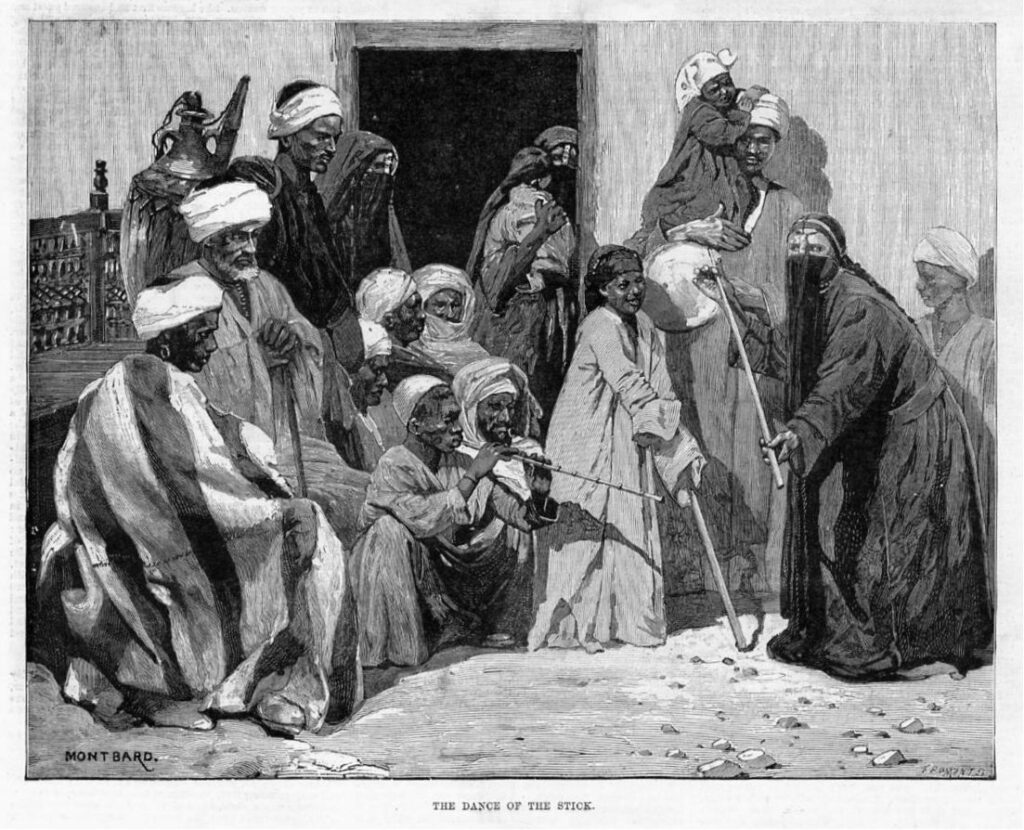

Raqs at-taḥṭīb, which literally in Arabic means “fighting dance,” is performed by male dancers of the Sa’id (a region in southern/Upper Egypt) with a bamboo fighting staff—‘assaya, nabbout, or shoum in Arabic¹—up to six feet long. It is believed that this particular dance might be traced back to ancient Egypt, where Pharaonic armies used the staff in combat training and as a weapon on the battlefield. Throughout Egyptian history, men have used staffs for herding, protection, and walking. It isn’t clear, however, whether or not men in Pharaonic times danced with the staff. That particular practice might have evolved much later. Edward W. Lane saw a “game” of stick fighting during his travels in Egypt, saying that sometimes “two peasants contend with each other, for mere amusement, or for a trifling wager or reward […] with staves, five or six feet long: the object of each is to strike his adversary on the head.”² Today, it is still described as a game—in fact, many practitioners do not refer to it as raqs (dance), but rather as ‘iba (game)—a highly ritualized mock fight accompanied by music. It is performed frequently at a variety of occassions, such as mawlid festivals, weddings, welcoming parties, and harvest festivals.³ The core movements of this dance include graceful posturing and mock fighting, and is sometimes performed on horseback with staffs up to twelve feet (3.7m) long.⁴ The music used features the tabl baladi (a large bass drum also called davul in Turkey or tapan in the Balkans) and mizmar (a double-reeded folk oboe).

Despite the stereotype of the Sai’di people—that of an uneducated, unsophisticated peasant—Sai’di dance is actually one of the most cherished in Egypt, and a source of national pride.⁵ In the 1960s Egyptian choreographer Mahmoud Reda theatricalized and polished this folkdance for stage. Although traditionally women do not dance with the taḥṭīb, he also included women in his taḥṭīb dance, having them playfully borrow the man’s ‘assaya and dance with it for just a few moments during the performance.⁶

Originally inspired by Mahmoud Reda, female Oriental dancers around the world have made the raqs al-’assaya (Arabic: stick dance) an integral part of their belly dance shows. Instead of the bamboo staff, the Oriental dancer uses a crooked cane or smaller stick than what the men use, and the dancer’s movements imitate and poke fun at the men’s version of the dance.⁷ When performed by women, the dance is typically less aggressive, more flirtatious and playful, and performed without an opponent. This dance, according to Candace Bordelon, “conjures images of both the virile Saidi male and the innocent female.”⁸ While a long cane or staff is ripe for Freudian analysis, the cane is never overtly used as a symbol of manhood. Dancers will also balance the cane on their head, hips, shoulders, and/or chest. When part of a longer show, an Oriental dancer typically changes out of her two-piece bedla, and into a baladi dress or even a men’s galabiyya to reflect the folkloric nature of the performance.⁹

The content from this post is excerpted from The Salimpour School of Belly Dance Compendium. Volume 1: Beyond Jamila’s Articles. published by Suhaila International in 2015. This Compendium is an introduction to several topics raised in Jamila’s Article Book.

If you would like to make a citation for this article, we suggest the following format: Keyes, A. (2023). Raqs at-Taḥṭīb. Salimpour School. Retrieved insert retrieval date, from https://suhaila.com/raqs-at-taḥṭib/

1 Magda Saleh, “Nizzawi and Tahtib: The Egyptian Stick Dance,” Arabesque 7:1 (1981) 9.

2 Lane, Manners and Customs, 357.

3 Saleh, “Nizzawi and Tahtib,” 9.

4 AlZayer, Middle Eastern Dance, 34.

5 Candace Bordelon, “Finding ‘the Feeling’: Oriental Dance, Musiqa al-Gadid, and Tarab,” in Belly Dance Around the World: New Communities, Performance and Identity, ed. Caitlin E. McDonald and Barbara Sellers-Young, (Jefferson, North Carolina, McFarland & Company, 2013), 38.

6 Shems, “Cane Dance – Saidi, Baladi or Lebanese,” accessed December 28, 2013, http://www.shemsdance.com/articles/cane-dance-saidi-baladi-or-lebanese/.

7 Shems, “Cane Dance.”

8 Bordelon, “Finding ‘the Feeling,’” 37.

9 AlZayer, Middle Eastern Dance, 34.